The College of Pennsylvania’s Penn Museum in Philadelphia will open its new, 2,000-sq.-ft Native North America Gallery on Saturday (22 November) after two years of planning and improvement.

An all-day opening celebration—that includes performances, workshops, talks, demonstrations and storytelling—will inaugurate the brand new long-term exhibition with a strengthened deal with Native American histories. The gallery replaces its earlier iteration, an exhibition titled Native American Voices: The Folks—Right here and Now, which opened in 2014 however didn’t absolutely replicate the 4 areas of Native American tribes it sought to current.

The previous gallery was curated by the museum’s Lucy Fowler Williams in collaboration with round 80 Native American consultants. However the area felt “fragmented”, Williams says. This time round, she and co-curator Megan C. Kassabaum—with their backgrounds in cultural anthropology and anthropological archaeology, respectively—labored carefully with eight Native American curators, who helped decide which tales ought to be informed within the exhibition.

“We made a aware choice to not draw back from representing the moments of rupture, loss and betrayal that Native communities have confronted; these tales are important,” Williams says. “However we additionally needed to focus on resilience and energy inside these histories.”

On show within the Northwest part, a Naaxein (Chilkat Tlingit blanket) ceremonial gown Photograph: Kellie Bell for the Penn Museum

Moderately than calling Native curators “advisers” or “consultants”, the museum was “intentional about recognising them as curators”, Williams provides. “The work they had been doing was curatorial, and we needed that mirrored in how we referred to them—not simply as a symbolic shift however as a structural one. That language issues; it shapes how everybody else within the establishment sees and treats the collaboration.”

Leaders on the museum hope that nearer partnership with Native students will set a benchmark for a way establishments work with tribes, assist to advance tips round moral museum practices and spark constructive conversations round repatriation that immediate guests to interact with complexities round colonialism, cultural resilience and the moral stewardship of Native objects.

“This was a chance to consider how we are able to put these tales in dialog with our assortment and the historic report, then ensure that the voices of latest Native communities are main the cost,” Kassabaum says. “I hope that, years from now, guests will see that these relationships have additionally matured and adjusted.”

The consulting curators are Jeremy Johnson (Lenape, Absentee Shawnee and Peoria), cultural schooling director for the Delaware Tribe of Indians; RaeLynn Butler (Creek), tradition and humanities secretary for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation; the archaeologists Beau Carroll (Jap Band of Cherokee Indians) and Mary Weahkee (Santa Clara Pueblo); the artwork historian Nadia Sethi (Alutiiq/Ninilchik); the Zuni cultural specialist Christopher Lewis (Badger Clan and Corn Clan); Huna Indian Affiliation tradition heritage director Darlene See (Tlingít); and the tribal historic-preservation officer Joseph Aguilar (San Ildefonso Pueblo).

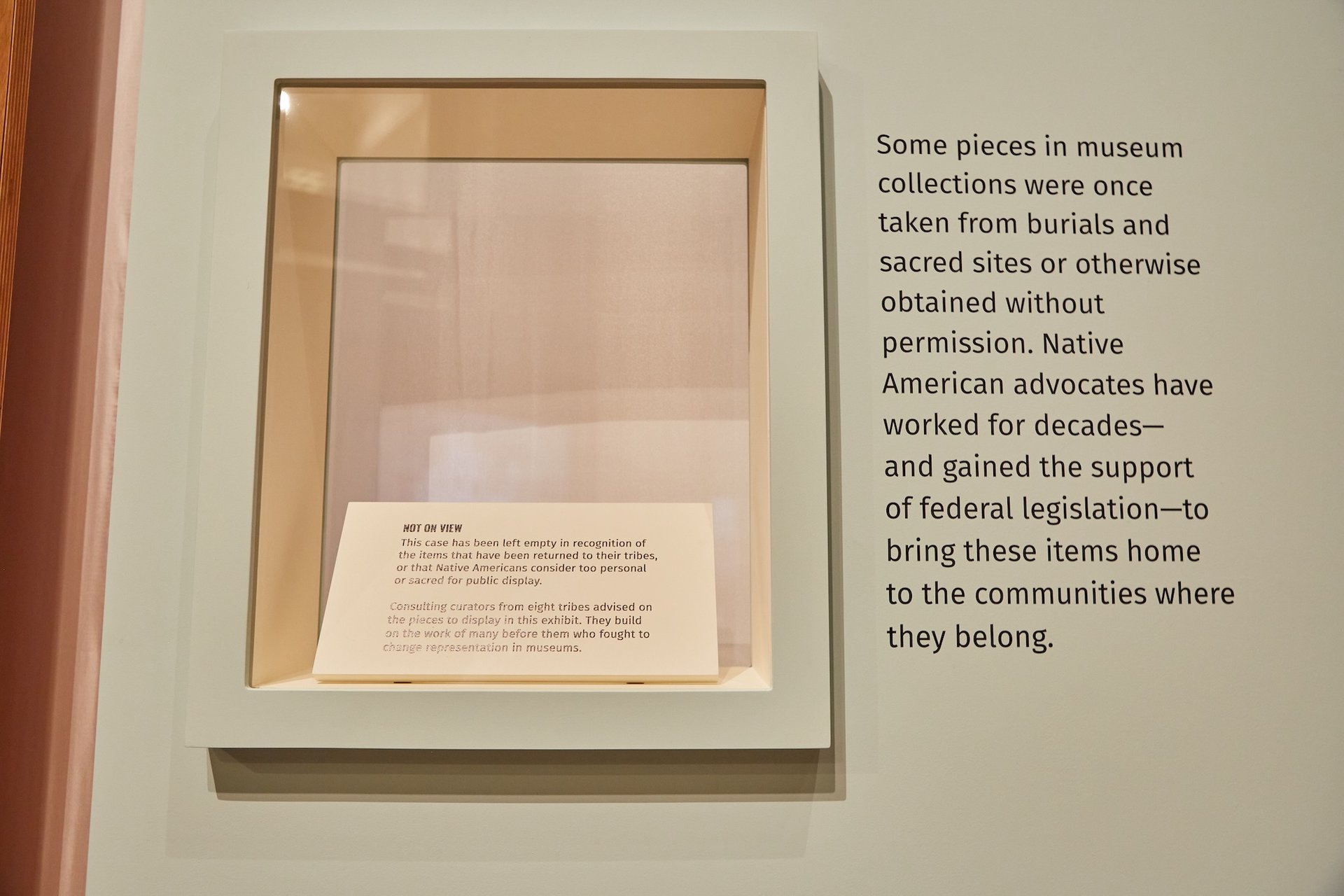

An empty show case supplies a second for considerate reflection about repatriation and honouring Native views about which gadgets are applicable for show Photograph: Quinn R. Brown for the Penn Museum

Aguilar, a College of Pennsylvania alum who additionally labored on the 2014 setup, says the previous gallery was “outdated however nonetheless snug”, given that there have been few museums the place he “felt welcome as a Native particular person”. For the gallery’s present iteration, Aguilar helped conceive the presentation of an empty vitrine, the very first thing guests encounter within the new gallery. It’s a gesture recognising each ongoing repatriation efforts in museums and the objects that tribes really feel are inappropriate to exhibit.

“The Penn Museum has many culturally delicate supplies that, within the eyes of the communities, shouldn’t be displayed,” he says. “Moderately than omitting them with out reference, we needed to acknowledge them. An empty case says greater than nothing in any respect. It serves as a educating second for guests. Repatriation was additionally an essential a part of the narrative we needed to carry throughout.”

Through the years, the Penn Museum has been scrutinised for its repatriation processes. A number of objects in its 160,000-piece North American artwork assortment, which signify Native American and First Nations Canadian communities, stay beneath evaluate. Ever for the reason that Native American Graves Safety and Repatriation Act (Nagpra) was enacted in 1990—mandating that federally funded museums within the US make their holdings obtainable for repatriation requests—the museum has labored with greater than 130 tribes to finish 56 repatriations, ensuing within the return of greater than 1,600 human stays, funerary objects, gadgets of cultural patrimony and different holdings.

Aguilar says that his expertise as a co-curator of the brand new gallery has “fulfilled” his expectations for a way museums ought to have interaction with Native communities. “There’s a lot museums can do. They’ve the capability—but it surely’s not about assets, it’s about dedication,” he says. “This venture is an instance of a museum shifting in the appropriate route. Museums should associate, not simply collaborate; there must be an equal stake in stewardship of collections or the creation of exhibitions. Actual funding in communities—monetary, programmatic and long-term—is critical.”

Multimedia choices and hands-on interactives play a serious function within the new Native North America Gallery Photograph: Quinn R. Brown for the Penn Museum

The Native North America Gallery centres first-person Native views, analyzing the political, linguistic, spiritual and inventive nuances that form tribal cultures. It mixes up to date artwork, equivalent to works by the artists Brenda Mallory (Cherokee) and Preston Singletary (Tlingit), with round 250 historic and archaeological objects—together with replicas of fragile supplies. The gallery additionally corrects the interpretation of objects that had been beforehand inaccurately labeled within the assortment database, equivalent to a “shaman’s wand” that Native curators decided was truly a doll.

There are components of the gallery that goal to develop on how tribal areas have been traditionally represented in museums. For instance, reasonably than specializing in pottery to signify Southwestern tribes, the curators determined to function sometimes seen objects that maintain equal ceremonial and sensible which means. These embrace clothes and baskets made from yucca and fibre that relate to the tribes’ relationship with the high-desert setting and its crops. As well as, the gallery options interactive components, like stations for studying phrases in Native languages or conventional weaving methods.

The museum’s director, Christopher Woods, says the disclosing of the gallery upfront of the 250th anniversary of the founding of the US subsequent 12 months, and through Native American Heritage Month, supplies a chance for guests to “replicate on American historical past by Indigenous views” and “amplify the significance of Indigenous values and communities that we all know inhabited this land lengthy earlier than the nation was based”.

Woods provides that the museum stays “steadfast” in its mission, regardless of cuts to federal funding for the humanities beneath president Donald Trump’s administration. The Penn Museum obtained quite a few donations to understand the venture, together with from the Boston-area real-estate mogul Lewis Heafitz and his spouse, Ina. Woods believes that donors noticed the present political state of affairs “not as a setback because of the world altering round us however as a name to motion”, recognising the significance of “inclusive, traditionally grounded storytelling as nationwide narratives are being contested and rewritten”.